What if I told you that there was a brown army with real world power looking for an opportunity to help you get to where you want to go in?

My Gs, it’s true.

And I have proof. A lot of it. And I’m rolling it out in a series called, Operation Level Up. Check out the inaugural piece with HR consultant Raul Pereyra who provides solid advice for advancing your career during Covid.

In this article, we connect with John Fraire, a university administrator with an Ivy league degree, a a penchant for exploring Mexican American history and willingness to give back…to you, even.

Meet John (who happens to drink Mestizo coffee, if you hadn’t heard).

- John, you’ve had a unique experience during the pandemic, tell us about that.

I was living in Seattle when in 2018 I was offered a one year interim senior leadership position at Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU), a Chicago located Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). Part of the arrangement was they put me up in one of their university’s on campus apartments, fully furnished and equipped. That’s where I lived when COVID started and I stayed there alone until the start of 2021. I guess you could say I was living in a college dorm. I was with students, had to go down the hall to do my laundry, and lived on the fifth floor. I finally moved out and now live in Indiana with family.

2. Tell us about your college experience.

In 1973, I was one of 15 Mexican Americans/Chicanos who enrolled at Harvard, Class of 1977. Prior to that year, Harvard had admitted only one or two Mexican Americans/Chicanos a year. So, we joke among ourselves that we were a social experiment. “Would Harvard survive if 15 Mexicans came to campus all at once?” We did all right and Harvard is still standing.

Back in 1996, I wrote “Recruiting Minority Students in Post Modern America” for the College Board Magazine in which I detail some of my experiences at Harvard. One of the things I said in the article was that Harvard was racist, even by 1973 standards, and that includes faculty and staff, not just students. Yet, I was determined to stay and succeed. I felt if I dropped out or quit it would reflect badly on other Chicanos who followed me. I also believed it would be disrespectful to my family, community and others who sacrificed so I could attend a place like Harvard. They would have been disappointed if I let racism and a challenging environment defeat me.

3.How did your Harvard uniquely prepare you? Were there any blindspots in your education?

One critical way that Harvard prepared me is that I learned what it meant to come from a working class family. My father worked in the steel mills and my mother was a school secretary. I could clearly see the privilege and class difference in my classmates. After my junior year I decided to take a year off, something about a third of Harvard students do, but unlike my classmates who spend their year off back packing in Europe or interning with a senator their daddy knows, I went back home and worked in the steel mills where most people in NW Indiana work, Mexican and non Mexican.

My parents had helped my two older brothers in college, and there were three siblings following me, so I wanted to make some money to help out my parents. I was also not happy at Harvard and wanted a change of scenery. While working in one of the mills (Inland Steel where my dad worked), I also studied labor history, assisted by my brother Rock’s friend, Dr. James Lane, a Gary historian and Indiana University history professor. That year was also the year Ed Sadlowski challenged the old union bosses when he ran for presidency of the United Steelworkers (USW) union in what I think was the last attempt in this country by rank ‘n file unionists in the traditional industries to seize power. So, I returned to Harvard much more confident and with a much stronger sense of my class background. I even wrote about the USW union election for my Harvard senior thesis. You can say one of the most elite and privileged institutions in the country helped teach me about my class background.

As for blindspots?

My first couple of years at Harvard were difficult for me because I was intimidated and clearly experiencing the impostor syndrome. I felt I was an admissions mistake. Everyone else seemed so much smarter than me. That is why that year off, going home, working in the mills, and studying labor history was so transformational for me. By time I graduated, I was no longer intimidated and felt empowered by knowing and appreciating my history better.

4. Tell us about your career trajectory.

Upon graduation in 1978, I was hired to be on the Harvard undergraduate admissions staff and worked there for six years, primarily helping to advance their recruitment of Mexican Americans/Chicanos and other students of color. Even though I understood Harvard to be a training ground for the elite and powerful and did not enjoy my student experience there, I still believed people of color needed to attend such institutions. Along with Connie Rice, an African American woman who was hired at the same time I was, I helped establish Harvard’s minority recruitment programs and increased the diversity of their enrollments.

After my time at Harvard, I worked several years full time as a political and community organizer, and when I needed to return to a “regular” job, it made sense to turn to recruiting and admissions. It was still enjoyable work and helping students get a college education was both noble and needed. I was able to move up the ladder, so to speak, from director of admissions (Brooklyn College), dean of admissions (Western Michigan), associate vice president for enrollment (Truman State), and vice president for student affairs and enrollment (Washington State).

5. What can Latinos who work in higher education do to advance the prospects of the next generation of both students and administrators?

I was a consultant for the Gates Millennium Scholars program for minority students for the 16 years the program existed. My job was to train and supervise the primarily Latino group of educators who reviewed the applications from Latino students. It was important work, but what was developmental professionally for me was that I was able to meet and work with Latinos in higher ed throughout the country. I am still in contact with many of those folks. It is a good network. Many social media groups focusing on Latinos in higher exist, and they are growing. On Facebook there is Latinx in Student Affairs, Latinx Scholars, Chicana and Chicano Studies and more, and more on LinkedIn. I encourage Latinos interested and involved in higher education to network and support each other as much as possible. I also encourage Latino educators to consider positions in finance and enrollment. Those areas involve revenue and are critical positions for a university. We need more diversity in those positions. I have not been able to find exact statistics, but it is a good bet that I am only one of a handful of Mexican Americans/Chicanos who is a full vice president of enrollment at a major university. There should be many more.

6. You write. Why?

A significant part of my life has centered on community and political organizing. A couple of times I stepped out of my job in higher ed to work full time as a political organizer. I was part of the independent political movement for many years, and worked with many other political people. Much of that work was based out of New York City, so I was living there. It was shocking to me at the time that many of my fellow organizers had no clue or understanding of Mexican Americans or Chicanos. Most of them assumed Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, a larger population in New York city, were interchangeable. And if they had some knowledge Mexicans, they stereotypically believed we lived only in Texas, California and the Southwest, and worked in agriculture and lawn maintenance.

Mexican Americans were not steelworkers from Gary, Indiana. My response was to write a play with my brother Gabriel, a writer living in northern California (gabrielfraire.com), called Who Will Dance with Pancho Villa? It is a semi autobiographical, magical realism play that combined my interest in Pancho Villa and my desire to teach people about Chicanos from the Midwest. Since then, my brother and I have co-authored other plays and productions about the Midwest Chicano urban experience.

What was fun was that for many years I had already been collecting the oral histories of my mother, grandmother and other elderly Mexicans from Indiana Harbor, Indiana. And in 1992, the Señoras of Yesteryear, a group of elderly Mexican women, including my mother who was the group’s vice president, produced Mexican American Harbor Lights, a community history book of the Mexican community in Indiana Harbor. It is filled with text, lists, dates, photographs, and personal stories of their families’ migration to Indiana Harbor and other key experiences, all from women. Some of the stories were part of Who Will Dance with Pancho Villa. I continued to collect the oral histories of my mother and the early Mexican residents of the area.

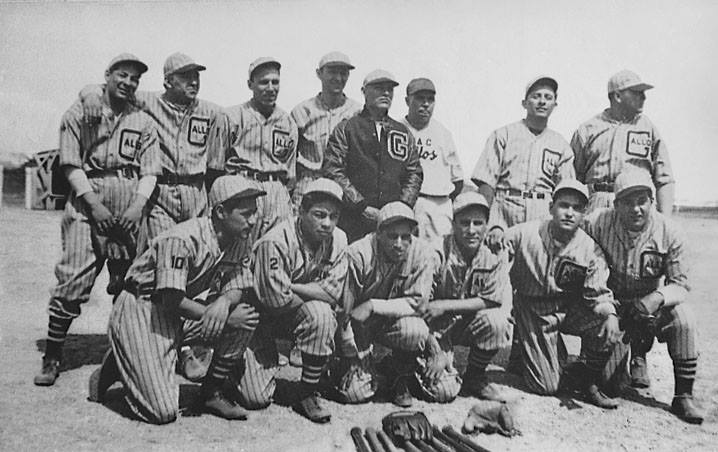

The oral histories were part of my doctoral dissertation which focused on the formation of Mexican men and women’s baseball in Indiana Harbor in the 1930’s and 40’s and the simultaneous development of their Mexicanidad and U.S./American identity. My mother was one of the star players for the girls’ softball team called Las Gallinas. I continue to write the cultural history of the Mexican community of Northwest Indiana.

7. Tell us about your interest in Oscar Zeta Acosta.

When I was a teenager I had no problem reading articles (especially ones about sports and World War II), but for some reason books were difficult for me to read and understand. The only two books I was able to read completely were the Autobiography of Malcolm X and the Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo. I connected connected culturally with Oscar Zeta Acosta and the concept and imagery of the Brown Buffalo. Having worked many years in the independent electoral movement I like that his history involved electoral work. For me, a Brown Buffalo represents quiet strength, power, culture and it connects with the indigenous part of the Chicano identity. I believe strongly in Black and Brown unity, but I also firmly believe if we are to make significant social and structural change in this country, there needs to be a greater unity of Chicanos and the Native American community. I think the Brown Buffalo represents that. And I thoroughly enjoyed the The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo documentary.

8. What’s the connection between you, baseball and Mexican American history?

Baseball is part of the social and cultural history of the Mexican community in Indiana Harbor, Indiana, my home community. Baseball played a significant developmental role for the early Mexican residents who were youth and teenagers during the 1930’s and early 40’s, my parents and their generation, the Greatest Generation. The early Mexican residents of Indiana Harbor, like my parents, did not play baseball as some sort of Americanization process, or as a method to become more incorporated into U.S./American society and become less Mexican. They played baseball as a developmental community activity and as a way to interact with other communities. It was their ability to continually develop their Mexican ethnic identity, not lose it or become more American, that in later years was a critical factor in their ability to become an integral and contributing community in Northwest Indiana. In short, they became more U.S./American by becoming more Mexican.

9. Where can people stay connected to your work?

I can be reached at my website brownbuffalonotes.com And if anyone would like to read my article “Mexicans Playing Baseball in Indiana Harbor, 1925-1942,” published by the Indiana Magazine of History, 2014; or “Recruiting Minority Students in Post Modern America,” by the College Board Magazine, 1996, just email me and I will send you a copy.